Psittacosaurus is a genus of dinosaurs that is not that well known, but has gained some recognition recently because of a specimen discovered in China which was found to have its skin pattern intact.

.png)

As a litle bit of background, Psittacosaurs are actually considered the archetype of Cerotopsians (a group that includes Tricerotops) because they had many of the traits of later Cerotopsians. For example, Psittacosaurs had frills, short snouts, a parrot-like beak, a high placement of their nostrils on their skulls, and only 3 functional digits in the hands, which are all features shared with later Cerotopsians (Lucas 2006).

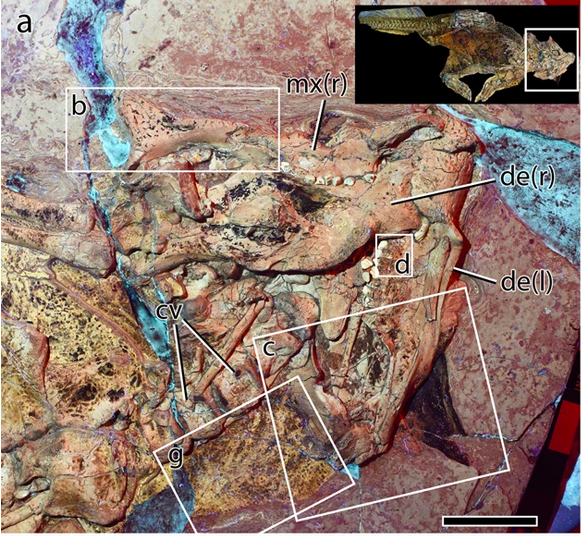

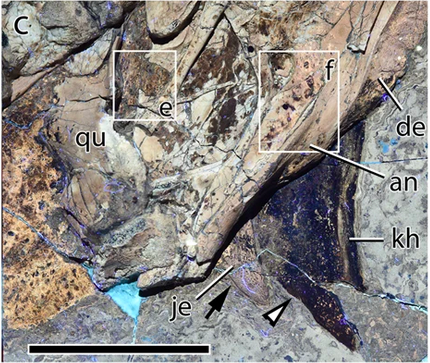

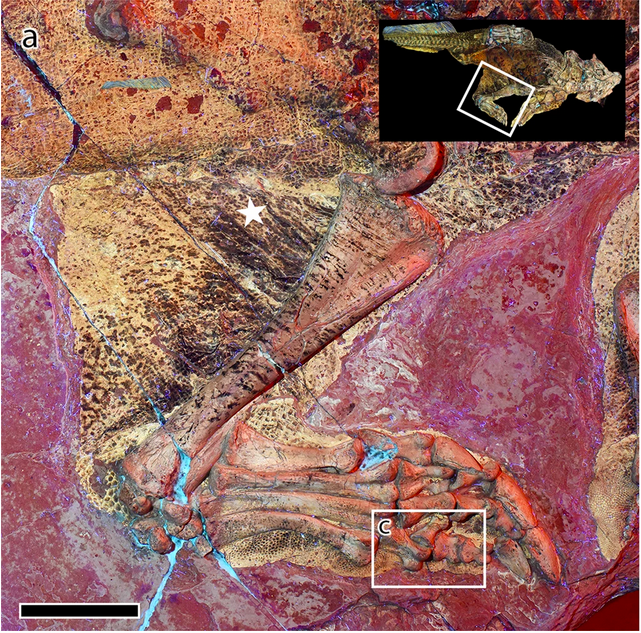

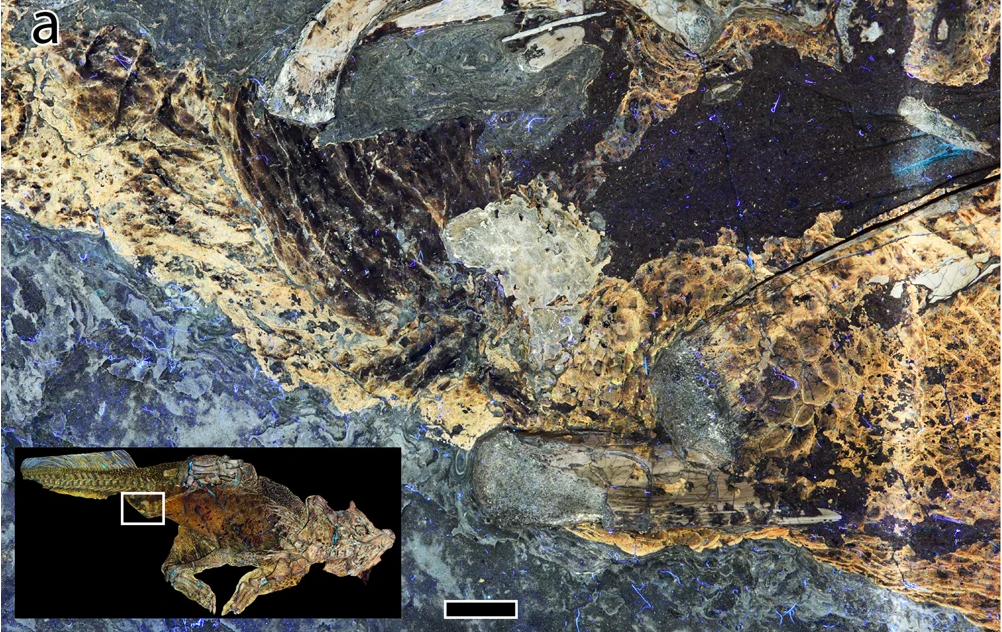

From the aforementioned specimen, scientists were able to see that Psittacosaurus did, in fact, have scaly skin (Bell et al. 2022). They then went on to describe the size and shape of different scales over the animal's body—with some of those findings shared here.

Starting at the head, the scientists noted that each cheekbone had a horn that projected off of it, with the top surface of the horn appearing to have been covered in keratin (the same material found in human nails and in rhinosaurus horns) (Bell et al. 2022). In fact, they were able to determine that this "keratin sheath" likely projected at least 23 mm beyond the tip of the bone of these horns (Bell et al. 2022). They also found that the scales around the bases of the horn had roughly hexagonal shapes (Bell et al. 2022).

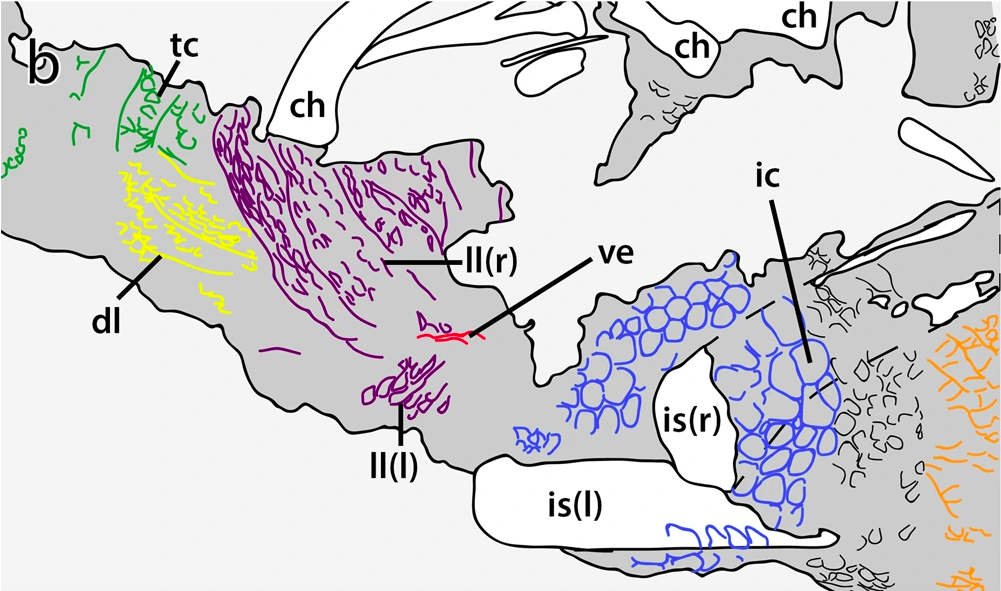

On the throat, they noted that the majority of the scales were oval to circle shaped while on the neck, the scales were circular to slightly polygonal (multi-sided) (Bell et al. 2022).

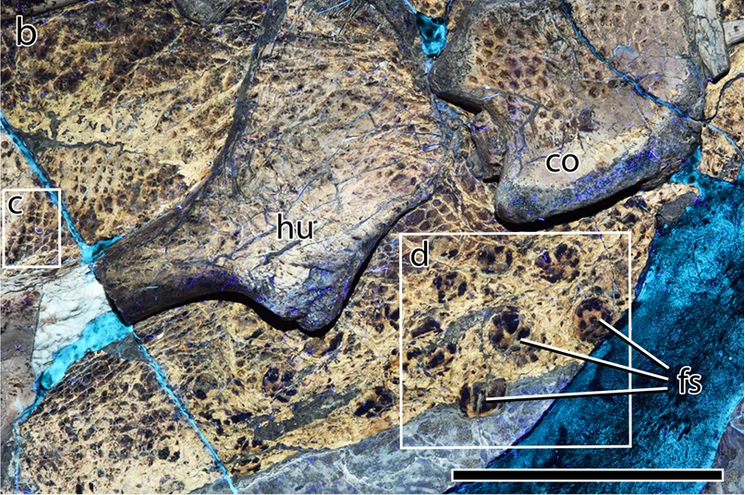

On the front limbs and pectoral girdle the scales were varying in shape, but were generally multi-sided (Bell et al. 2022). Tthe scales on the front facing part of the limbs were found to run parallel with the length of the legs (Bell et al. 2022).

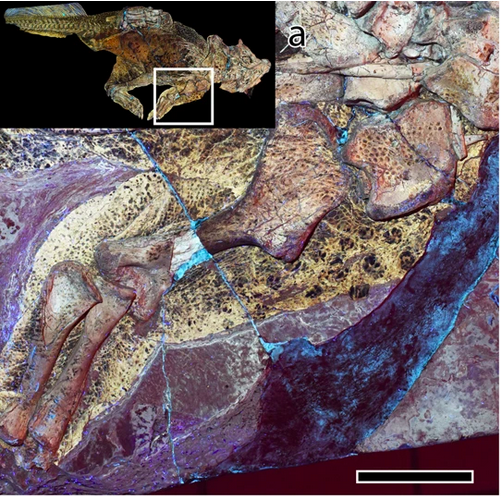

The skin covering the back of the upper leg was covered in scales forming a repeating pattern of a central multi-sided scale, surrounded by 5 or 6 smaller triagular scales (Bell et al. 2022).

In the area of the rib cage, the scales are approximately diamond shaped with the points of the diamonds aligned with the length of the animal (Bell et al. 2022). These scales are themselves surrounded by circular and irregularly shaped scales (Bell et al. 2022).

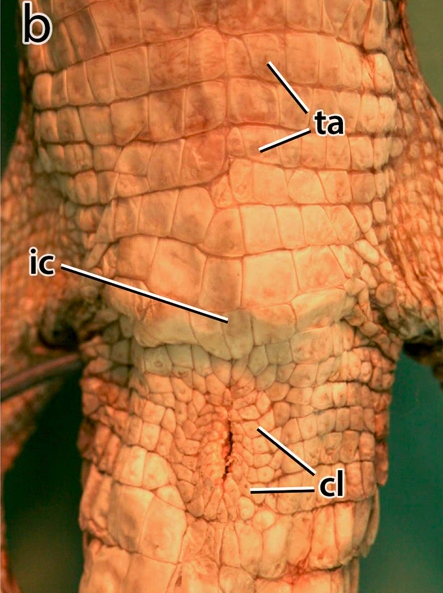

In the abdominal region, the scales were found to be four-sided and arranged into bands that go across the width of the abdomen—the authors note that this is similar to the pattern seen in modern crocodylians, lizards, worm lizards, and snakes (Bell et al. 2022).

This pattern of scales is broken down the middle by a row of paired four-sided scales that run the length of the abdomen (Bell et al. 2022).

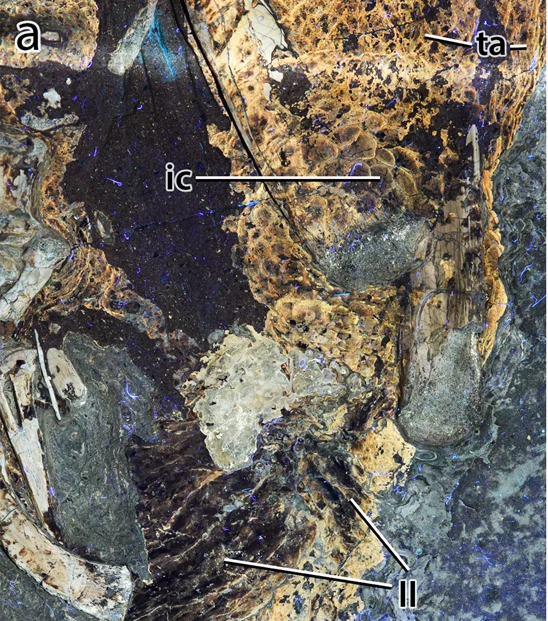

On the hindlimbs, the scales were found to form a pattern consisting of a central circular-ish scale surrounded by smaller triangular scales (Bell et al. 2022). In particular, on the ankles, the scales were found to be larger than those found elsewhere on the body and were diamond shaped (Bell et al. 2022). The size of the scales, along with the fact that the integument over the ankle appeared swollen, suggests there may have been a callous around the ankle (Bell et al. 2022).

One of the standout finds from this study was that the researchers were able to see the cloaca much more clearly (Bell et al. 2022). For context, the cloaca is an organ found in birds and reptiles through which urine and feces exit the body in reptiles and birds, and through which reproduction can take place (Bell et al. 2022). In the specimen, the authors found that the cloaca was shaped like the letter "Y" -with the tail of the "Y" pointing toward the head of the animal (Bell et al. 2022).

Furthermore, the pattern of scaling of the cloaca was found to be similar to that seen in crocodylians—the scales of the cloaca had a rosette pattern and the scales surrounding the cloaca were shaped like rectangles and were arranged in rows (Bell et al. 2022). The authors postulated that this could indicate that the internal genital anatomy of Psittacosaurus was also similar to crocodylians (Bell et al. 2022). This is exciting because it is otherwise very difficult to determine what the internal anatomy of dinosaurs looked like because soft tissues are not preserved well in the fossil record.

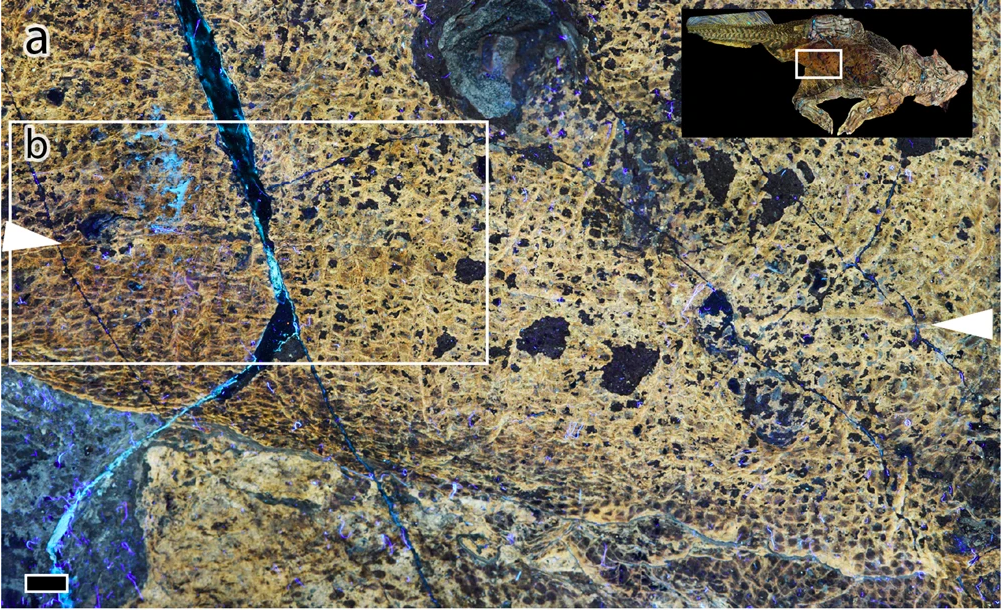

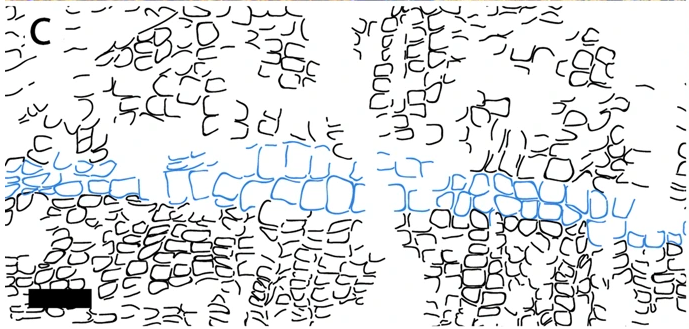

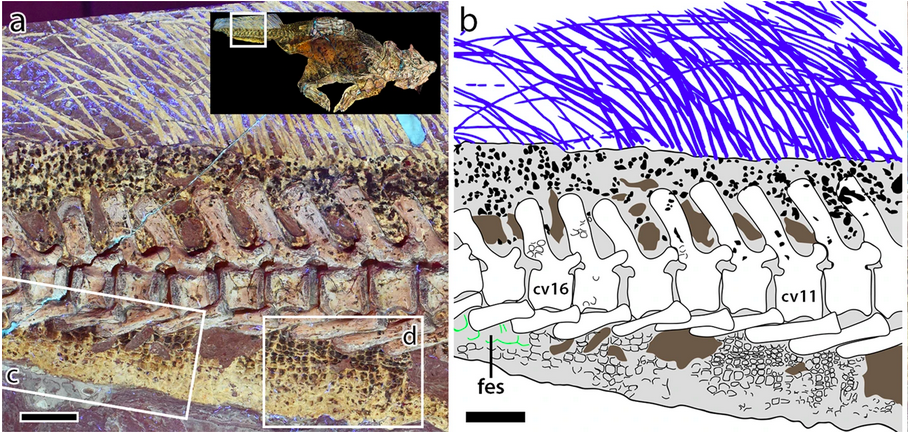

As some bonus trivia, the dark area below the tail in Exhibit 1 represents the skin covering the ischial bones (bones of the pelvis on which the animal sat) that had large pigmented scales—which is represented as darkened patches below the tail (Bell et al. 2022). The tracing of these callouses is seen in blue Exhibit 14.

Another surprising find on this Psittacosaurus specimen was the presence of bristles that seemed to come out of the Psittacosaurus' tail (Bell et al. 2022). These bristles were found in a 235mm (23.5cm) long strip along the dorsal surface of the proximal third of the tail (Bell et al. 2022). The bristles themselves were about 16cm in length and were found to taper to points at their ends (Bell et al. 2022). The authors suggested that these bristles may represent a form of display such as the ornamental feathers seen in a peacock (Bell et al. 2022). The interesting thing about the preservation of these bristles is that it may mean that other dinosaur species also had interesting physical traits that were simply not preserved in the fossil record (Bell et al. 2022).

Another interesting fact that was gleaned from the examination of skeletons of P. lujiatunensis (another species of Psittacosaurus) was that it appeared that as the animals grew, their front legs became proportionally shorter than their hind limbs. (Zhao et al. 2013). They determined this by comparing the lengths of the front and hind limbs of the animals at different ages—they noted that the size of the forelimbs decreased as compared to the hindlimbs as the animals grew (Zhao et al. 2013).

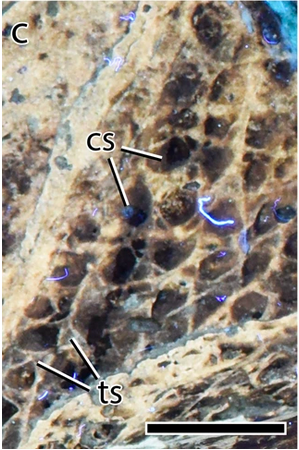

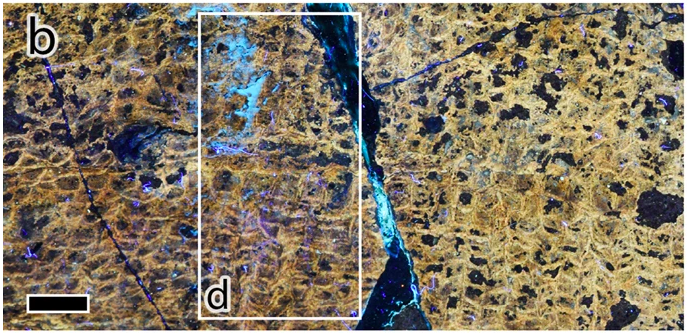

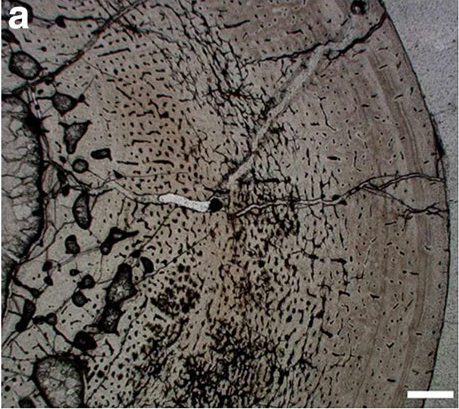

By looking at the fossils under a microscope, the authors also found that the hind limbs bones were highly vascularized (meaning that there was a lot of blood vessels which supplied nutrients to the bone) in the early growth period of these animals and that the pattern of the "canals" that the blood vessels would have run through in the bone changed from being more reticular (web-like) to becoming more longitudinal in the older specimens (Zhao et al. 2013). Based on the changes to the canal patterns, the researchers suggested that the hindlimbs started to grow more rapidly between three to six years of age in the animals—as indicated by the higher proportion of reticular canals as compared to longitudinal canals—although they acknowledge that the idea that canal patterns are related to bone growth requires further testing (Zhao et al. 2013). However, this study suggests that as hatchlings, P. lujiatunensis were quadrupedal (requiring four limbs for locomotion) and as adults they could have been bipedal (able to walk on two limbs) (Zhao et al. 2013). Indeed, the researchers note that there is increasing evidence that many dinosaur species shifted from a four-legged stance as juveniles to a two-legged stance as adults (Zhoa et al. 2013).

First published on: Sept. 12, 2023.